See the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for summaries of the available research on this topic.

The scope of this page is speech sound disorders with no known cause—historically called articulation and phonological disorders—in preschool and school-age children (ages 3–21).

Information about speech sound problems related to motor/neurological disorders, structural abnormalities, and sensory/perceptual disorders (e.g., hearing loss) is not addressed in this page.

See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Childhood Apraxia of Speech and Cleft Lip and Palate for information about speech sound problems associated with these two disorders. A Practice Portal page on dysarthria in children will be developed in the future.

Speech sound disorders is an umbrella term referring to any difficulty or combination of difficulties with perception, motor production, or phonological representation of speech sounds and speech segments—including phonotactic rules governing permissible speech sound sequences in a language.

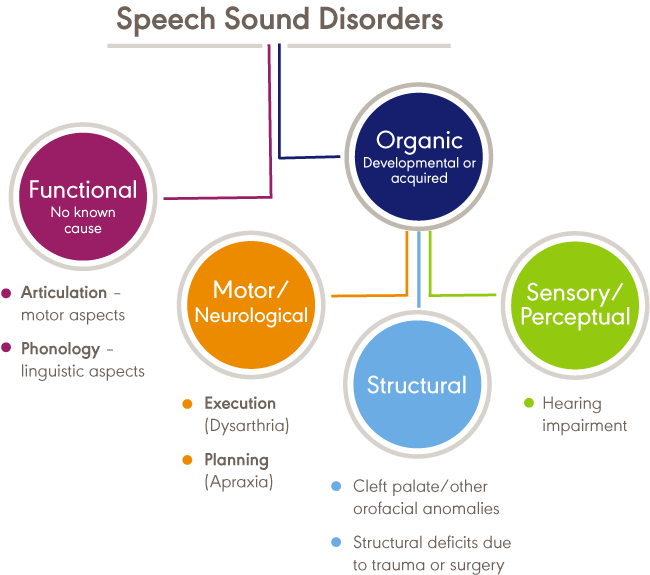

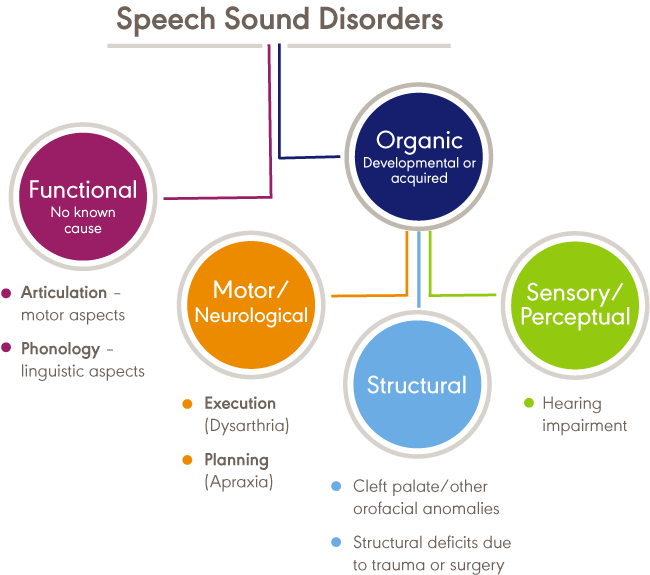

Speech sound disorders can be organic or functional in nature. Organic speech sound disorders result from an underlying motor/neurological, structural, or sensory/perceptual cause. Functional speech sound disorders are idiopathic—they have no known cause. See figure below.

Organic speech sound disorders include those resulting from motor/neurological disorders (e.g., childhood apraxia of speech and dysarthria), structural abnormalities (e.g., cleft lip/palate and other structural deficits or anomalies), and sensory/perceptual disorders (e.g., hearing loss).

Functional speech sound disorders include those related to the motor production of speech sounds and those related to the linguistic aspects of speech production. Historically, these disorders are referred to as articulation disorders and phonological disorders, respectively. Articulation disorders focus on errors (e.g., distortions and substitutions) in production of individual speech sounds. Phonological disorders focus on predictable, rule-based errors (e.g., fronting, stopping, and final consonant deletion) that affect more than one sound. It is often difficult to cleanly differentiate between articulation and phonological disorders; therefore, many researchers and clinicians prefer to use the broader term, "speech sound disorder," when referring to speech errors of unknown cause. See Bernthal, Bankson, and Flipsen (2017) and Peña-Brooks and Hegde (2015) for relevant discussions.

This Practice Portal page focuses on functional speech sound disorders. The broad term, "speech sound disorder(s)," is used throughout; articulation error types and phonological error patterns within this diagnostic category are described as needed for clarity.

Procedures and approaches detailed in this page may also be appropriate for assessing and treating organic speech sound disorders. See Speech Characteristics: Selected Populations [PDF] for a brief summary of selected populations and characteristic speech problems.

The incidence of speech sound disorders refers to the number of new cases identified in a specified period. The prevalence of speech sound disorders refers to the number of children who are living with speech problems in a given time period.

Estimated prevalence rates of speech sound disorders vary greatly due to the inconsistent classifications of the disorders and the variance of ages studied. The following data reflect the variability:

Signs and symptoms of functional speech sound disorders include the following:

Signs and symptoms may occur as independent articulation errors or as phonological rule-based error patterns (see ASHA's resource on selected phonological processes [patterns] for examples). In addition to these common rule-based error patterns, idiosyncratic error patterns can also occur. For example, a child might substitute many sounds with a favorite or default sound, resulting in a considerable number of homonyms (e.g., shore, sore, chore, and tore might all be pronounced as door; Grunwell, 1987; Williams, 2003a).

An accent is the unique way that speech is pronounced by a group of people speaking the same language and is a natural part of spoken language. Accents may be regional; for example, someone from New York may sound different than someone from South Carolina. Foreign accents occur when a set of phonetic traits of one language are carried over when a person learns a new language. The first language acquired by a bilingual or multilingual individual can influence the pronunciation of speech sounds and the acquisition of phonotactic rules in subsequently acquired languages. No accent is "better" than another. Accents, like dialects, are not speech or language disorders but, rather, only reflect differences. See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Multilingual Service Delivery in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology and Cultural Responsiveness.

Not all sound substitutions and omissions are speech errors. Instead, they may be related to a feature of a speaker's dialect (a rule-governed language system that reflects the regional and social background of its speakers). Dialectal variations of a language may cross all linguistic parameters, including phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. An example of a dialectal variation in phonology occurs with speakers of African American English (AAE) when a "d" sound is used for a "th" sound (e.g., "dis" for "this"). This variation is not evidence of a speech sound disorder but, rather, one of the phonological features of AAE.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) must distinguish between dialectal differences and communicative disorders and must

The cause of functional speech sound disorders is not known; however, some risk factors have been investigated.

Frequently reported risk factors include the following:

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) play a central role in the screening, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of persons with speech sound disorders. The professional roles and activities in speech-language pathology include clinical/educational services (diagnosis, assessment, planning, and treatment); prevention and advocacy; and education, administration, and research. See ASHA's Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology (ASHA, 2016).

Appropriate roles for SLPs include the following:

As indicated in the Code of Ethics (ASHA, 2023), SLPs who serve this population should be specifically educated and appropriately trained to do so.

See the Assessment section of the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

Screening is conducted whenever a speech sound disorder is suspected or as part of a comprehensive speech and language evaluation for a child with communication concerns. The purpose of the screening is to identify individuals who require further speech-language assessment and/or referral for other professional services.

Screening typically includes

Screening may result in

The acquisition of speech sounds is a developmental process, and children often demonstrate "typical" errors and phonological patterns during this acquisition period. Developmentally appropriate errors and patterns are taken into consideration during assessment for speech sound disorders in order to differentiate typical errors from those that are unusual or not age appropriate.

The comprehensive assessment protocol for speech sound disorders may include an evaluation of spoken and written language skills, if indicated. See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Spoken Language Disorders and Written Language Disorders.

Assessment is accomplished using a variety of measures and activities, including both standardized and nonstandardized measures, as well as formal and informal assessment tools. See ASHA's resource on assessment tools, techniques, and data sources.

SLPs select assessments that are culturally and linguistically sensitive, taking into consideration current research and best practice in assessing speech sound disorders in the languages and/or dialect used by the individual (see, e.g., McLeod et al., 2017). Standard scores cannot be reported for assessments that are not normed on a group that is representative of the individual being assessed.

SLPs take into account cultural and linguistic speech differences across communities, including

Consistent with the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework (ASHA, 2016a; WHO, 2001), a comprehensive assessment is conducted to identify and describe

See ASHA's Person-Centered Focus on Function: Speech Sound Disorder [PDF] for an example of assessment data consistent with ICF.

Assessment may result in

The case history typically includes gathering information about

See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Cultural Responsiveness for guidance on taking a case history with all clients.

The oral mechanism examination evaluates the structure and function of the speech mechanism to assess whether the system is adequate for speech production. This examination typically includes assessment of

A hearing screening is conducted during the comprehensive speech sound assessment, if one was not completed during the screening.

Hearing screening typically includes

The speech sound assessment uses both standardized assessment instruments and other sampling procedures to evaluate production in single words and connected speech.

Single-word testing provides identifiable units of production and allows most consonants in the language to be elicited in a number of phonetic contexts; however, it may or may not accurately reflect production of the same sounds in connected speech.

Connected speech sampling provides information about production of sounds in connected speech using a variety of talking tasks (e.g., storytelling or retelling, describing pictures, normal conversation about a topic of interest) and with a variety of communication partners (e.g., peers, siblings, parents, and clinician).

Assessment of speech includes evaluation of the following:

Severity is a qualitative judgment made by the clinician indicating the impact of the child's speech sound disorder on functional communication. It is typically defined along a continuum from mild to severe or profound. There is no clear consensus regarding the best way to determine severity of a speech sound disorder—rating scales and quantitative measures have been used.

A numerical scale or continuum of disability is often used because it is time-efficient. Prezas and Hodson (2010) use a continuum of severity from mild (omissions are rare; few substitutions) to profound (extensive omissions and many substitutions; extremely limited phonemic and phonotactic repertoires). Distortions and assimilations occur in varying degrees at all levels of the continuum.

A quantitative approach (Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1982a, 1982b) uses the percentage of consonants correct (PCC) to determine severity on a continuum from mild to severe.

To determine PCC, collect and phonetically transcribe a speech sample. Then count the total number of consonants in the sample and the total number of correct consonants. Use the following formula:

PCC = (correct consonants/total consonants) × 100

A PCC of 85–100 is considered mild, whereas a PCC of less than 50 is considered severe. This approach has been modified to include a total of 10 such indices, including percent vowels correct (PVC; Shriberg, Austin, Lewis, McSweeny, & Wilson, 1997).

Intelligibility is a perceptual judgment that is based on how much of the child's spontaneous speech the listener understands. Intelligibility can vary along a continuum ranging from intelligible (message is completely understood) to unintelligible (message is not understood; Bernthal et al., 2017). Intelligibility is frequently used when judging the severity of the child's speech problem (Kent, Miolo, & Bloedel, 1994; Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1982b) and can be used to determine the need for intervention.

Intelligibility can vary depending on a number of factors, including

Rating scales and other estimates that are based on perceptual judgments are commonly used to assess intelligibility. For example, rating scales sometimes use numerical ratings like 1 for totally intelligible and 10 for unintelligible, or they use descriptors like not at all, seldom, sometimes, most of the time, or always to indicated how well speech is understood (Ertmer, 2010).

A number of quantitative measures also have been proposed, including calculating the percentage of words understood in conversational speech (e.g., Flipsen, 2006; Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1980). See also Kent et al. (1994) for a comprehensive review of procedures for assessing intelligibility.

Coplan and Gleason (1988) developed a standardized intelligibility screener using parent estimates of how intelligible their child sounded to others. On the basis of the data, expected intelligibility cutoff values for typically developing children were as follows:

See the Resources section for resources related to assessing intelligibility and life participation in monolingual children who speak English and in monolingual children who speak languages other than English.

Stimulability is the child's ability to accurately imitate a misarticulated sound when the clinician provides a model. There are few standardized procedures for testing stimulability (Glaspey & Stoel-Gammon, 2007; Powell & Miccio, 1996), although some test batteries include stimulability subtests.

Stimulability testing helps determine

Speech perception is the ability to perceive differences between speech sounds. In children with speech sound disorders, speech perception is the child's ability to perceive the difference between the standard production of a sound and his or her own error production—or to perceive the contrast between two phonetically similar sounds (e.g., r/w, s/ʃ, f/θ).

Speech perception abilities can be tested using the following paradigms:

Young children might not be able to follow directions for standardized tests, might have limited expressive vocabulary, and might produce words that are unintelligible. Other children, regardless of age, may produce less intelligible speech or be reluctant to speak in an assessment setting.

Strategies for collecting an adequate speech sample with these populations include

Sometimes, the speech sound disorder is so severe that the child's intended message cannot be understood. However, even when a child's speech is unintelligible, it is usually possible to obtain information about his or her speech sound production.

Assessment of a bilingual individual requires an understanding of both linguistic systems because the sound system of one language can influence the sound system of another language. The assessment process must identify whether differences are truly related to a speech sound disorder or are normal variations of speech caused by the first language.

When assessing a bilingual or multilingual individual, clinicians typically

See phonemic inventories and cultural and linguistic information across languages and ASHA's Practice Portal page on Multilingual Service Delivery in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology. See the Resources section for information related to assessing intelligibility and life participation in monolingual children who speak English and in monolingual children who speak languages other than English.

Phonological processing is the use of the sounds of one's language (i.e., phonemes) to process spoken and written language (Wagner & Torgesen, 1987). The broad category of phonological processing includes phonological awareness, phonological working memory, and phonological retrieval.

All three components of phonological processing (see definitions below) are important for speech production and for the development of spoken and written language skills. Therefore, it is important to assess phonological processing skills and to monitor the spoken and written language development of children with phonological processing difficulties.

Language testing is included in a comprehensive speech sound assessment because of the high incidence of co-occurring language problems in children with speech sound disorders (Shriberg & Austin, 1998).

Typically, the assessment of spoken language begins with a screening of expressive and receptive skills; a full battery is performed if indicated by screening results. See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Spoken Language Disorders for more details.

Difficulties with the speech processing system (e.g., listening, discriminating speech sounds, remembering speech sounds, producing speech sounds) can lead to speech production and phonological awareness difficulties. These difficulties can have a negative impact on the development of reading and writing skills (Anthony et al., 2011; Catts, McIlraith, Bridges, & Nielsen, 2017; Leitão & Fletcher, 2004; Lewis et al., 2011).

For typically developing children, speech production and phonological awareness develop in a mutually supportive way (Carroll, Snowling, Stevenson, & Hulme, 2003; National Institute for Literacy, 2009). As children playfully engage in sound play, they eventually learn to segment words into separate sounds and to "map" sounds onto printed letters.

The understanding that sounds are represented by symbolic code (e.g., letters and letter combinations) is essential for reading and spelling. When reading, children have to be able to segment a written word into individual sounds, based on their knowledge of the code and then blend those sounds together to form a word. When spelling, children have to be able to segment a spoken word into individual sounds and then choose the correct code to represent these sounds (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000; Pascoe, Stackhouse, & Wells, 2006).

Components of the written language assessment include the following, depending on the child's age and expected stage of written language development:

See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Written Language Disorders for more details.

See the Treatment section of the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

The broad term "speech sound disorder(s)" is used in this Portal page to refer to functional speech sound disorders, including those related to the motor production of speech sounds (articulation) and those related to the linguistic aspects of speech production (phonological).

It is often difficult to cleanly differentiate between articulation and phonological errors or to differentially diagnose these two separate disorders. Nevertheless, we often talk about articulation error types and phonological error types within the broad diagnostic category of speech sound disorder(s). A single child might show both error types, and those specific errors might need different treatment approaches.

Historically, treatments that focus on motor production of speech sounds are called articulation approaches; treatments that focus on the linguistic aspects of speech production are called phonological/language-based approaches.

Articulation approaches target each sound deviation and are often selected by the clinician when the child's errors are assumed to be motor based; the aim is correct production of the target sound(s).

Phonological/language-based approaches target a group of sounds with similar error patterns, although the actual treatment of exemplars of the error pattern may target individual sounds. Phonological approaches are often selected in an effort to help the child internalize phonological rules and generalize these rules to other sounds within the pattern (e.g., final consonant deletion, cluster reduction).

Articulation and phonological/language-based approaches might both be used in therapy with the same individual at different times or for different reasons.

Both approaches for the treatment of speech sound disorders typically involve the following sequence of steps:

Approaches for selecting initial therapy targets for children with articulation and/or phonological disorders include the following:

See ASHA's Person-Centered Focus on Function: Speech Sound Disorder [PDF] for an example of goal setting consistent with ICF.

In addition to selecting appropriate targets for therapy, SLPs select treatment strategies based on the number of intervention goals to be addressed in each session and the manner in which these goals are implemented. A particular strategy may not be appropriate for all children, and strategies may change throughout the course of intervention as the child's needs change.

"Target attack" strategies include the following:

The following are brief descriptions of both general and specific treatments for children with speech sound disorders. These approaches can be used to treat speech sound problems in a variety of populations. See Speech Characteristics: Selected Populations [PDF] for a brief summary of selected populations and characteristic speech problems.

Treatment selection will depend on a number of factors, including the child's age, the type of speech sound errors, the severity of the disorder, and the degree to which the disorder affects overall intelligibility (Williams, McLeod, & McCauley, 2010). This list is not exhaustive, and inclusion does not imply an endorsement from ASHA.

Contextual utilization approaches recognize that speech sounds are produced in syllable-based contexts in connected speech and that some (phonemic/phonetic) contexts can facilitate correct production of a particular sound.

Contextual utilization approaches may be helpful for children who use a sound inconsistently and need a method to facilitate consistent production of that sound in other contexts. Instruction for a particular sound is initiated in the syllable context(s) where the sound can be produced correctly (McDonald, 1974). The syllable is used as the building block for practice at more complex levels.

For example, production of a "t" may be facilitated in the context of a high front vowel, as in "tea" (Bernthal et al., 2017). Facilitative contexts or "likely best bets" for production can be identified for voiced, velar, alveolar, and nasal consonants. For example, a "best bet" for nasal consonants is before a low vowel, as in "mad" (Bleile, 2002).

Phonological contrast approaches are frequently used to address phonological error patterns. They focus on improving phonemic contrasts in the child's speech by emphasizing sound contrasts necessary to differentiate one word from another. Contrast approaches use contrasting word pairs as targets instead of individual sounds.

There are four different contrastive approaches—minimal oppositions, maximal oppositions, treatment of the empty set, and multiple oppositions.

The complexity approach is a speech production approach based on data supporting the view that the use of more complex linguistic stimuli helps promote generalization to untreated but related targets.

The complexity approach grew primarily from the maximal oppositions approach. However, it differs from the maximal oppositions approach in a number of ways. Rather than selecting targets on the basis of features such as voice, place, and manner, the complexity of targets is determined in other ways. These include hierarchies of complexity (e.g., clusters, fricatives, and affricates are more complex than other sound classes) and stimulability (i.e., sounds with the lowest levels of stimulability are most complex). In addition, although the maximal oppositions approach trains targets in contrasting word pairs, the complexity approach does not. See Baker and Williams (2010) and Peña-Brooks and Hegde (2015) for detailed descriptions of the complexity approach.

A core vocabulary approach focuses on whole-word production and is used for children with inconsistent speech sound production who may be resistant to more traditional therapy approaches.

Words selected for practice are those used frequently in the child's functional communication. A list of frequently used words is developed (e.g., based on observation, parent report, and/or teacher report), and a number of words from this list are selected each week for treatment. The child is taught his or her "best" word production, and the words are practiced until consistently produced (Dodd, Holm, Crosbie, & McIntosh, 2006).

The cycles approach targets phonological pattern errors and is designed for children with highly unintelligible speech who have extensive omissions, some substitutions, and a restricted use of consonants.

Treatment is scheduled in cycles ranging from 5 to 16 weeks. During each cycle, one or more phonological patterns are targeted. After each cycle has been completed, another cycle begins, targeting one or more different phonological patterns. Recycling of phonological patterns continues until the targeted patterns are present in the child's spontaneous speech (Hodson, 2010; Prezas & Hodson, 2010).

The goal is to approximate the gradual typical phonological development process. There is no predetermined level of mastery of phonemes or phoneme patterns within each cycle; cycles are used to stimulate the emergence of a specific sound or pattern—not to produce mastery of it.

Distinctive feature therapy focuses on elements of phonemes that are lacking in a child's repertoire (e.g., frication, nasality, voicing, and place of articulation) and is typically used for children who primarily substitute one sound for another. See Place, Manner and Voicing Chart for English Consonants (Roth & Worthington, 2018).

Distinctive feature therapy uses targets (e.g., minimal pairs) that compare the phonetic elements/features of the target sound with those of its substitution or some other sound contrast. Patterns of features can be identified and targeted; producing one target sound often generalizes to other sounds that share the targeted feature (Blache & Parsons, 1980; Blache et al., 1981; Elbert & McReynolds, 1978; McReynolds & Bennett, 1972; Ruder & Bunce, 1981).

Metaphon therapy is designed to teach metaphonological awareness—that is, the awareness of the phonological structure of language. This approach assumes that children with phonological disorders have failed to acquire the rules of the phonological system.

The focus is on sound properties that need to be contrasted. For example, for problems with voicing, the concept of "noisy" (voiced) versus "quiet" (voiceless) is taught. Targets typically include processes that affect intelligibility, can be imitated, or are not seen in typically developing children of the same age (Dean, Howell, Waters, & Reid, 1995; Howell & Dean, 1994).

Naturalist speech intelligibility intervention addresses the targeted sound in naturalistic activities that provide the child with frequent opportunities for the sound to occur. For example, using a McDonald's menu, signs at the grocery store, or favorite books, the child can be asked questions about words that contain the targeted sound(s). The child's error productions are recast without the use of imitative prompts or direct motor training. This approach is used with children who are able to use the recasts effectively (Camarata, 2010).

Nonspeech oral–motor therapy involves the use of oral-motor training prior to teaching sounds or as a supplement to speech sound instruction. The rationale behind this approach is that (a) immature or deficient oral-motor control or strength may be causing poor articulation and (b) it is necessary to teach control of the articulators before working on correct production of sounds. Consult systematic reviews of this treatment to help guide clinical decision making (see, e.g., Lee & Gibbon, 2015 [PDF]; McCauley, Strand, Lof, Schooling, & Frymark, 2009). See also the Treatment section of the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map filtered for Oral–Motor Exercises.

Speech sound perception training is used to help a child acquire a stable perceptual representation for the target phoneme or phonological structure. The goal is to ensure that the child is attending to the appropriate acoustic cues and weighting them according to a language-specific strategy (i.e., one that ensures reliable perception of the target in a variety of listening contexts).

Recommended procedures include (a) auditory bombardment in which many and varied target exemplars are presented to the child, sometimes in a meaningful context such as a story and often with amplification, and (b) identification tasks in which the child identifies correct and incorrect versions of the target (e.g., "rat" is a correct exemplar of the word corresponding to a rodent, whereas "wat" is not).

Tasks typically progress from the child judging speech produced by others to the child judging the accuracy of his or her own speech. Speech sound perception training is often used before and/or in conjunction with speech production training approaches. See Rvachew, 1994; Rvachew et al., 2004; Rvachew, Rafaat, & Martin, 1999; Wolfe, Presley, & Mesaris, 2003.

Traditionally, the speech stimuli used in these tasks are presented via live voice by the SLP. More recently, computer technology has been used—an advantage of this approach is that it allows for the presentation of more varied stimuli representing, for example, multiple voices and a range of error types.

Techniques used in therapy to increase awareness of the target sound and/or provide feedback about placement and movement of the articulators include the following:

When treating a bilingual or multilingual individual with a speech sound disorder, the clinician is working with two or more different sound systems. Although there may be some overlap in the phonemic inventories of each language, there will be some sounds unique to each language and different phonemic rules for each language.

One linguistic sound system may influence production of the other sound system. It is the role of the SLP to determine whether any observed differences are due to a true communication disorder or whether these differences represent variations of speech associated with another language that a child speaks.

Strategies used when designing a treatment protocol include

Criteria for determining eligibility for services in a school setting are detailed in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEA). In accordance with these criteria, the SLP needs to determine

Examples of the adverse effect on educational performance include the following:

Eligibility for speech-language pathology services is documented in the child's individualized education program, and the child's goals and the dismissal process are explained to parents and teachers. For more information about eligibility for services in the schools, see ASHA's resources on eligibility and dismissal in schools, IDEA Part B Issue Brief: Individualized Education Programs and Eligibility for Services, and 2011 IDEA Part C Final Regulations.

If a child is not eligible for services under IDEA, they may still be eligible to receive services under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504. 29 U.S.C. § 701 (1973). See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Documentation in Schools for more information about Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

Dismissal from speech-language pathology services occurs once eligibility criteria are no longer met—that is, when the child's communication problem no longer adversely affects academic achievement and functional performance.

Speech difficulties sometimes persist throughout the school years and into adulthood. Pascoe et al. (2006) define persisting speech difficulties as "difficulties in the normal development of speech that do not resolve as the child matures or even after they receive specific help for these problems" (p. 2). The population of children with persistent speech difficulties is heterogeneous, varying in etiology, severity, and nature of speech difficulties (Dodd, 2005; Shriberg et al., 2010; Stackhouse, 2006; Wren, Roulstone, & Miller, 2012).

A child with persisting speech difficulties (functional speech sound disorders) may be at risk for

Intervention approaches vary and may depend on the child's area(s) of difficulty (e.g., spoken language, written language, and/or psychosocial issues).

In designing an effective treatment protocol, the SLP considers

Children with persisting speech difficulties may continue to have problems with oral communication, reading and writing, and social aspects of life as they transition to post-secondary education and vocational settings (see, e.g., Carrigg, Baker, Parry, & Ballard, 2015). The potential impact of persisting speech difficulties highlights the need for continued support to facilitate a successful transition to young adulthood. These supports include the following:

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 provide protections for students with disabilities who are transitioning to postsecondary education. The protections provided by these acts (a) ensure that programs are accessible to these students and (b) provide aids and services necessary for effective communication (U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2011).

For more information about transition planning, see ASHA's resource on Postsecondary Transition Planning.

See the Service Delivery section of the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

In addition to determining the type of speech and language treatment that is optimal for children with speech sound disorders, SLPs consider the following other service delivery variables that may have an impact on treatment outcomes:

Technology can be incorporated into the delivery of services for speech sound disorders, including the use of telepractice as a format for delivering face-to-face services remotely. See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Telepractice.

The combination of service delivery factors is important to consider so that children receive optimal intervention intensity to ensure that efficient, effective change occurs (Baker, 2012; Williams, 2012).

Adler-Bock, M., Bernhardt, B. M., Gick, B., & Bacsfalvi, P. (2007). The use of ultrasound in remediation of North American English /r/ in 2 adolescents. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 128–139.

Altshuler, M. W. (1961). A therapeutic oral device for lateral emission. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 26, 179–181.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016a). Code of ethics [Ethics]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (20016b). Scope of practice in speech-language-pathology [Scope of Practice]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, P.L. 101-336, 42 U.S.C. §§ 12101 et seq.

Anthony, J. L., Aghara, R. G., Dunkelberger, M. J., Anthony, T. I., Williams, J. M., & Zhang, Z. (2011). What factors place children with speech sound disorders at risk for reading problems? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 146–160.

Baker, E. (2012). Optimal intervention intensity. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14, 401–409.

Baker, E., & Williams, A. L. (2010). Complexity approaches to intervention. In S. F. Warren & M. E. Fey (Series Eds.). & A. L. Williams, S. McLeod, & R. J. McCauley (Volume Eds.), Intervention for speech sound disorders in children (pp. 95–115). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Bernthal, J., Bankson, N. W., & Flipsen, P., Jr. (2017). Articulation and phonological disorders: Speech sound disorders in children. New York, NY: Pearson.

Blache, S., & Parsons, C. (1980). A linguistic approach to distinctive feature training. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 11, 203–207.

Blache, S. E., Parsons, C. L., & Humphreys, J. M. (1981). A minimal-word-pair model for teaching the linguistic significant difference of distinctive feature properties. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46, 291–296.

Black, L. I., Vahratian, A., & Hoffman, H. J. (2015). Communication disorders and use of intervention services among children aged 3–17 years; United States, 2012 (NHS Data Brief No. 205). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Bleile, K. (2002). Evaluating articulation and phonological disorders when the clock is running. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11, 243–249.

Byers Brown, B., Bendersky, M., & Chapman, T. (1986). The early utterances of preterm infants. British Journal of Communication Disorders, 21, 307–320.

Camarata, S. (2010). Naturalistic intervention for speech intelligibility and speech accuracy. In A. L. Williams, S. McLeod, & R. J. McCauley (Eds.), Interventions for speech sound disorders in children (pp. 381–406). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Campbell, T. F., Dollaghan, C. A., Rockette, H. E., Paradise, J. L., Feldman, H. M., Shriberg, L. D., . . . Kurs-Lasky, M. (2003). Risk factors for speech delay of unknown origin in 3-year-old children. Child Development, 74, 346–357.

Carrigg, B., Baker, E., Parry, L., & Ballard, K. J. (2015). Persistent speech sound disorder in a 22-year-old male: Communication, educational, socio-emotional, and vocational outcomes. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 16, 37–49.

Carroll, J. M., Snowling, M. J., Stevenson, J., & Hulme, C. (2003). The development of phonological awareness in preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 39, 913–923.

Catts, H. W., McIlraith, A., Bridges, M. S., & Nielsen, D. C. (2017). Viewing a phonological deficit within a multifactorial model of dyslexia. Reading and Writing, 30, 613–629.

Coplan, J., & Gleason, J. R. (1988). Unclear speech: Recognition and significance of unintelligible speech in preschool children. Pediatrics, 82, 447–452.

Crowe, K., & McLeod, S. (2020). Children’s English consonant acquisition in the United States: A review. American Journal of Speech-Language

Pathology, 29(4), 2155-2169. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00168.

Dagenais, P. A. (1995). Electropalatography in the treatment of articulation/phonological disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 28, 303–329.

Dean, E., Howell, J., Waters, D., & Reid, J. (1995). Metaphon: A metalinguistic approach to the treatment of phonological disorder in children. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 9, 1–19.

Dodd, B. (2005). Differential diagnosis and treatment of children with speech disorder. London, England: Whurr.

Dodd, B., Holm, A., Crosbie, S., & McIntosh, B. (2006). A core vocabulary approach for management of inconsistent speech disorder. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 8, 220–230.

Eadie, P., Morgan, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Eecen, K. T., Wake, M., & Reilly, S. (2015). Speech sound disorder at 4 years: Prevalence, comorbidities, and predictors in a community cohort of children. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 57, 578–584.

Elbert, M., & McReynolds, L. V. (1978). An experimental analysis of misarticulating children's generalization. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 21, 136–149.

Ertmer, D. J. (2010). Relationship between speech intelligibility and word articulation scores in children with hearing loss. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 1075–1086.

Everhart, R. (1960). Literature survey of growth and developmental factors in articulation maturation. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 25, 59–69.

Fabiano-Smith, L., & Goldstein, B. A. (2010). Phonological acquisition in bilingual Spanish–English speaking children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 160–178.

Felsenfeld, S., McGue, M., & Broen, P. A. (1995). Familial aggregation of phonological disorders: Results from a 28-year follow-up. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 38, 1091–1107.

Fey, M. (1986). Language intervention with young children. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Flipsen, P. (2006). Measuring the intelligibility of conversational speech in children. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 20, 202–312.

Flipsen, P. (2015). Emergence and prevalence of persistent and residual speech errors. Seminars in Speech Language, 36, 217–223.

Fox, A. V., Dodd, B., & Howard, D. (2002). Risk factors for speech disorders in children. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 37, 117–132.

Gibbon, F., Stewart, F., Hardcastle, W. J., & Crampin, L. (1999). Widening access to electropalatography for children with persistent sound system disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 8, 319–333.

Gierut, J. A. (1989). Maximal opposition approach to phonological treatment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 54, 9–19.

Gierut, J. A. (1990). Differential learning of phonological oppositions. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 33, 540–549.

Gierut, J. A. (1992). The conditions and course of clinically induced phonological change. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35, 1049–1063.

Gierut, J. A. (2007). Phonological complexity and language learnability. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 6–17.

Glaspey, A. M., & Stoel-Gammon, C. (2007). A dynamic approach to phonological assessment. Advances in Speech-Language Pathology, 9, 286–296.

Goldstein, B. A., & Fabiano, L. (2007, February 13). Assessment and intervention for bilingual children with phonological disorders. The ASHA Leader, 12, 6–7, 26–27, 31.

Grunwell, P. (1987). Clinical phonology (2nd ed.). London, England: Chapman and Hall.

Hitchcock, E. R., McAllister Byun, T., Swartz, M., & Lazarus, R. (2017). Efficacy of electropalatography for treating misarticulations of /r/. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26, 1141–1158.

Hodson, B. (2010). Evaluating and enhancing children's phonological systems: Research and theory to practice. Wichita, KS: PhonoComp.

Howell, J., & Dean, E. (1994). Treating phonological disorders in children: Metaphon—Theory to practice (2nd ed.). London, England: Whurr.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, P. L. 108-446, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1400 et seq. Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov/

Kent, R. D., Miolo, G., & Bloedel, S. (1994). The intelligibility of children's speech: A review of evaluation procedures. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 3, 81–95.

Law, J., Boyle, J., Harris, F., Harkness, A., & Nye, C. (2000). Prevalence and natural history of primary speech and language delay: Findings from a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 35, 165–188.

Lee, A. S. Y., & Gibbon, F. E. (2015). Non-speech oral motor treatment for children with developmental speech sound disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015 (3), 1–42.

Lee, S. A. S., Wrench, A., & Sancibrian, S. (2015). How to get started with ultrasound technology for treatment of speech sound disorders. Perspectives on Speech Science and Orofacial Disorders, 25, 66–80.

Leitão, S., & Fletcher, J. (2004). Literacy outcomes for students with speech impairment: Long-term follow-up. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 39, 245–256.

Leonti, S., Blakeley, R., & Louis, H. (1975, November). Spontaneous correction of resistant /ɚ/ and /r/ using an oral prosthesis. Paper presented at the annual convention of the American Speech and Hearing Association, Washington, DC.

Lewis, B. A., Avrich, A. A., Freebairn, L. A., Hansen, A. J., Sucheston, L. E., Kuo, I., . . . Stein, C. M. (2011). Literacy outcomes of children with early childhood speech sound disorders: Impact of endophenotypes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54, 1628–1643.

Locke, J. (1980). The inference of speech perception in the phonologically disordered child. Part I: A rationale, some criteria, the conventional tests. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 45, 431–444.

McAllister Byun, T., & Hitchcock, E. R. (2012). Investigating the use of traditional and spectral biofeedback approaches to intervention for /r/ misarticulation. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21, 207–221.

McCauley, R. J., Strand, E., Lof, G. L., Schooling, T., & Frymark, T. (2009). Evidence-based systematic review: Effects of nonspeech oral motor exercises on speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18, 343–360.

McCormack, J., McAllister, L., McLeod, S., & Harrison, L. (2012). Knowing, having, doing: The battles of childhood speech impairment. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 28, 141–157.

McDonald, E. T. (1974).Articulation testing and treatment: A sensory motor approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Stanwix House.

McLeod, S., & Crowe, K. (2018). Children's consonant acquisition in 27 languages: A cross-linguistic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27, 1546–1571.

McLeod, S., Verdon, S., & The International Expert Panel on Multilingual Children's Speech. (2017). Tutorial: Speech assessment for multilingual children who do not speak the same language(s) as the speech-language pathologist. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26, 691–708.

McNeill, B. C., & Hesketh, A. (2010). Developmental complexity of the stimuli included in mispronunciation detection tasks. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45, 72–82.

McReynolds, L. V., & Bennett, S. (1972). Distinctive feature generalization in articulation training. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 37, 462–470.

Morley, D. (1952). A ten-year survey of speech disorders among university students. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 17, 25–31.

National Institute for Literacy. (2009). Developing early literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel. A scientific synthesis of early literacy development and implications for intervention. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction [Report of the National Reading Panel]. Washington, DC: Author.

Overby, M.S., Trainin, G., Smit, A. B., Bernthal, J. E., & Nelson, R. (2012). Preliteracy speech sound production skill and later literacy outcomes: A study using the Templin Archive. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43, 97–115.

Pascoe, M., Stackhouse, J., & Wells, B. (2006). Persisting speech difficulties in children: Children's speech and literacy difficulties, Book 3. West Sussex, England: Whurr.

Peña-Brooks, A., & Hegde, M. N. (2015). Assessment and treatment of articulation and phonological disorders in children. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Peterson, R. L., Pennington, B. F., Shriberg, L. D., & Boada, R. (2009). What influences literacy outcome in children with speech sound disorder? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 1175-1188.

Powell, T. W., & Miccio, A. W. (1996). Stimulability: A useful clinical tool. Journal of Communication Disorders, 29, 237–253.

Preston, J. L., Brick, N., & Landi, N. (2013). Ultrasound biofeedback treatment for persisting childhood apraxia of speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22, 627–643.

Preston, J. L., McCabe, P., Rivera-Campos, A., Whittle, J. L., Landry, E., & Maas, E. (2014). Ultrasound visual feedback treatment and practice variability for residual speech sound errors. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57, 2102–2115.

Prezas, R. F., & Hodson, B. W. (2010). The cycles phonological remediation approach. In A. L. Williams, S. McLeod, & R. J. McCauley (Eds.), Interventions for speech sound disorders in children (pp. 137–158). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, P.L. No. 93-112, 29 U.S.C. § 794.

Roth, F. P., & Worthington, C. K. (2018). Treatment resource manual for speech-language pathology. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Ruder, K. F., & Bunce, B. H. (1981). Articulation therapy using distinctive feature analysis to structure the training program: Two case studies. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46, 59–65.

Rvachew, S. (1994). Speech perception training can facilitate sound production learning. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 37, 347–357.

Rvachew, S., & Bernhardt, B. M. (2010). Clinical implications of dynamic systems theory for phonological development. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19, 34–50.

Rvachew, S., Nowak, M., & Cloutier, G. (2004). Effect of phonemic perception training on the speech production and phonological awareness skills of children with expressive phonological delay. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13, 250–263.

Rvachew, S., Rafaat, S., & Martin, M. (1999). Stimulability, speech perception skills, and treatment of phonological disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 8, 33–43.

Shriberg, L. D. (1980). An intervention procedure for children with persistent /r/ errors. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 11, 102–110.

Shriberg, L. D., & Austin, D. (1998). Comorbidity of speech-language disorders: Implications for a phenotype marker for speech delay. In R. Paul (Ed.), The speech-language connection (pp. 73–117). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Shriberg, L. D., Austin, D., Lewis, B., McSweeny, J. L., & Wilson, D. L. (1997). The percentage of consonants correct (PCC) metric: Extensions and reliability data. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40, 708–722.

Shriberg, L. D., Fourakis, M., Hall, S. D., Karlsson, H. B., Lohmeier, H. L., McSweeny, J. L., . . . Wilson, D. L. (2010). Extensions to the speech disorders classification system (SDCS). Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 24, 795–824.

Shriberg, L. D., & Kwiatkowski, J. (1980). Natural Process Analysis (NPA): A procedure for phonological analysis of continuous speech samples. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Shriberg, L. D., & Kwiatkowski, J. (1982a). Phonological disorders II: A conceptual framework for management. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 47, 242–256.

Shriberg, L. D., & Kwiatkowski, J. (1982b). Phonological disorders III: A procedure for assessing severity of involvement. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 47, 256–270.

Shriberg, L. D., & Kwiatkowski, J. (1994). Developmental phonological disorders I: A clinical profile. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37, 1100–1126.

Shriberg, L. D., Tomblin, J. B., & McSweeny, J. L. (1999). Prevalence of speech delay in 6-year-old children and comorbidity with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 1461–1481.

Silva, P. A., Chalmers, D., & Stewart, I. (1986). Some audiological, psychological, educational and behavioral characteristics of children with bilateral otitis media with effusion. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 19, 165–169.

Stackhouse, J. (2006). Speech and spelling difficulties: Who is at risk and why? In M. Snowling & J. Stackhouse (Eds.), Dyslexia speech and language: A practitioner's handbook (pp. 15–35). West Sussex, England: Whurr.

Storkel, H. L. (2018). The complexity approach to phonological treatment: How to select treatment targets. Language, Speech, and Hearing Sciences in Schools, 49, 463–481.

Storkel, Holly. (2019). Using Developmental Norms for Speech Sounds as a Means of Determining Treatment Eligibility in Schools. Perspectives of

the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4, 67-75.

Teele, D. W., Klein, J. O., Chase, C., Menyuk, P., & Rosner, B. A. (1990). Otitis media in infancy and intellectual ability, school achievement, speech, and language at 7 years. Journal of Infectious Disease, 162, 685–694.

Tyler, A. A., & Tolbert, L. C. (2002). Speech-language assessment in the clinical setting. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11, 215–220.

U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights. (2011). Transition of students with disabilities to postsecondary education: A guide for high school educators. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/transitionguide.html

Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (1987). The nature of phonological processing and its causal role in the acquisition of reading skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 192–212.

Weiner, F. (1981). Treatment of phonological disability using the method of meaningful minimal contrast: Two case studies. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46, 97–103.

Williams, A. L. (2000a). Multiple oppositions: Case studies of variables in phonological intervention. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9,289–299.

Williams, A. L. (2000b). Multiple oppositions: Theoretical foundations for an alternative contrastive intervention approach. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9, 282–288.

Williams, A. L. (2003a). Speech disorders resource guide for preschool children. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Learning.

Williams, A. L. (2003b). Target selection and treatment outcomes. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education, 10, 12–16.

Williams, A. L. (2012). Intensity in phonological intervention: Is there a prescribed amount? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14, 456–461.

Williams, A. L., McLeod, S., & McCauley, R. J. (2010). Direct speech production intervention. In A. L. Williams, S. McLeod, & R. J. McCauley (Eds.), Interventions for speech sound disorders in children (pp. 27–39). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Wolfe, V., Presley, C., & Mesaris, J. (2003). The importance of sound identification training in phonological intervention. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12, 282–288.

World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

Wren, Y., Miller, L. L., Peters, T. J., Emond, A., & Roulstone, S. (2016). Prevalence and predictors of persistent speech sound disorder at eight years old: Findings from a population cohort study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59, 647–673.

Wren, Y. E., Roulstone, S. E., & Miller, L. L. (2012). Distinguishing groups of children with persistent speech disorder: Findings from a prospective population study. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 37, 1–10.

Content for ASHA's Practice Portal is developed through a comprehensive process that includes multiple rounds of subject matter expert input and review. ASHA extends its gratitude to the following subject matter experts who were involved in the development of the Speech Sound Disorders: Articulation and Phonology page:

The recommended citation for this Practice Portal page is: